The first feature of the definition of the Trinity in the Bible is the belief in one God. Christians believe in monotheism, which means they believe in the existence of only one true God, as opposed to polytheism, which believes in multiple gods. The Bible emphasizes this belief in various verses, such as Deuteronomy 6:4, which

Embark on a fascinating journey into the depths of biblical wisdom as we unravel the enigmatic concept of the Trinity. Discover the unique characteristics and profound significance that this divine mystery holds within the sacred scriptures. Brace yourself for a mind-blowing exploration that will leave you in awe of the remarkable value and spiritual revelations that the Trinity encompasses.

Unveiling the Divine Intricacy

At the core of Christian theology lies a concept that surpasses human comprehension – the Trinity. As we delve into the scriptures, we will unravel the intricately woven tapestry that portrays three distinct yet inseparable persons – the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Prepare to be amazed as you witness the unity and diversity within this divine triad.

The Unique Features of the Trinity

Intriguingly, each person within the Trinity carries a distinctive role, all harmoniously working towards a common purpose. Let us explore their individual attributes:

- The Father: Being the ultimate source of all creation, the Father displays unrivaled authority and wisdom. The one who loves unconditionally and nurtures all living beings.

- The Son: Jesus Christ, the embodiment of divine love and salvation. His sacrifice on the cross offers humanity the opportunity for redemption and everlasting life.

- The Holy Spirit: Representing the presence and power of God within believers, the Holy Spirit guides, comforts, and empowers humanity on their spiritual journey.

Together, these distinct persons form an inseparable unity, constantly interacting with one another in perfect harmony and love. This divine dance of relationship exhibits an awe-inspiring symbiotic bond.

What Does it Mean That God is a Trinity?

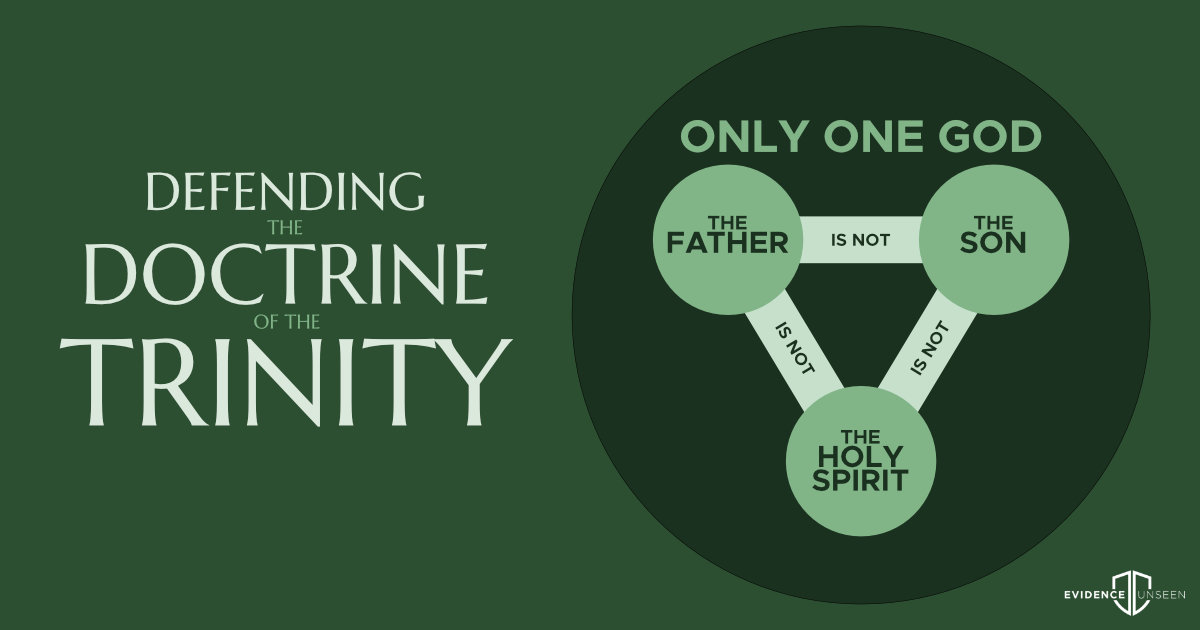

The doctrine of the Trinity means that there is one God who eternally exists as three distinct Persons — the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Stated differently, God is one in essence and three in person. These definitions express three crucial truths: (1) The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct Persons, (2) each Person is fully God, (3) there is only one God.

The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct Persons

The Bible speaks of the Father as God (Phil. 1:2), Jesus as God (Titus 2:13), and the Holy Spirit as God (Acts 5:3-4). Are these just three different ways of looking at God, or simply ways of referring to three different roles that God plays?

The answer must be no, because the Bible also indicates that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct Persons. For example, since the Father sent the Son into the world (John 3:16), He cannot be the same person as the Son. Likewise, after the Son returned to the Father (John 16:10), the Father and the Son sent the Holy Spirit into the world (John 14:26; Acts 2:33). Therefore, the Holy Spirit must be distinct from the Father and the Son.

In the baptism of Jesus, we see the Father speaking from heaven and the Spirit descending from heaven in the form of a dove as Jesus comes out of the water (Mark 1:10-11). In John 1:1 it is affirmed that Jesus is God and, at the same time, that He was “with God”- thereby indicating that Jesus is a distinct Person from God the Father (cf. also 1:18). And in John 16:13-15 we see that although there is a close unity between them all, the Holy Spirit is also distinct from the Father and the Son.

The fact that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct Persons means, in other words, that the Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Holy Spirit, and the Holy Spirit is not the Father. Jesus is God, but He is not the Father or the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is God, but He is not the Son or the Father. They are different Persons, not three different ways of looking at God.

The personhood of each member of the Trinity means that each Person has a distinct center of consciousness. Thus, they relate to each other personally — the Father regards Himself as “I,” while He regards the Son and Holy Spirit as “You.” Likewise the Son regards Himself as “I,” but the Father and the Holy Spirit as “You.”

Often it is objected that “If Jesus is God, then he must have prayed to himself while he was on earth.” But the answer to this objection lies in simply applying what we have already seen. While Jesus and the Father are both God, they are different Persons. Thus, Jesus prayed to God the Father without praying to Himself. In fact, it is precisely the continuing dialogue between the Father and the Son (Matthew 3:17; 17:5; John 5:19; 11:41-42; 17:1ff ) which furnishes the best evidence that they are distinct Persons with distinct centers of consciousness.

Sometimes the Personhood of the Father and Son is appreciated, but the Personhood of the Holy Spirit is neglected. Sometimes the Spirit is treated more like a “force” than a Person. But the Holy Spirit is not an it, but a He (see John 14:26; 16:7-15; Acts 8:16). The fact that the Holy Spirit is a Person, not an impersonal force (like gravity), is also shown by the fact that He speaks (Hebrews 3:7), reasons (Acts 15:28), thinks and understands (1 Corinthians 2:10-11), wills (1 Corinthians 12:11), feels (Ephesians 4:30), and gives personal fellowship (2 Corinthians 13:14).

These are all qualities of personhood. In addition to these texts, the others we mentioned above make clear that the Personhood of the Holy Spirit is distinct from the Personhood of the Son and the Father. They are three real persons, not three roles God plays.

Another serious error people have made is to think that the Father became the Son, who then became the Holy Spirit. Contrary to this, the passages we have seen imply that God always was and always will be three Persons. There was never a time when one of the Persons of the Godhead did not exist. They are all eternal.

While the three members of the Trinity are distinct, this does not mean that any is inferior to the other. Instead, they are all identical in attributes. They are equal in power, love, mercy, justice, holiness, knowledge, and all other qualities.

Each Person is fully God

If God is three Persons, does this mean that each Person is “one-third” of God? Does the Trinity mean that God is divided into three parts?

The Trinity does not divide God into three parts. The Bible is clear that all three Persons are each one hundred percent God. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all fully God. For example, it says of Christ that “in Him all the fullness of Deity dwells in bodily form” (Colossians 2:9).

We should not think of God as like a “pie” cut into three pieces, each piece representing a Person. This would make each Person less than fully God and thus not God at all. Rather, “the being of each Person is equal to the whole being of God.”[1] The divine essence is not something that is divided between the three persons, but is fully in all three persons without being divided into “parts.”

Thus, the Son is not one-third of the being of God, He is all of the being of God. The Father is not one-third of the being of God, He is all of the being of God. And likewise with the Holy Spirit. Thus, as Wayne Grudem writes, “When we speak of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit together we are not speaking of any greater being than when we speak of the Father alone, the Son alone, or the Holy Spirit alone.”[2]

There is only one God

If each Person of the Trinity is distinct and yet fully God, then should we conclude that there is more than one God? Obviously we cannot, for Scripture is clear that there is only one God: “There is no other God besides me, a righteous God and a Savior; there is none besides me. Turn to me and be saved, all the ends of the earth! For I am God, and there is no other” (Isaiah 45:21-22; see also 44:6-8; Exodus 15:11; Deuteronomy 4:35; 6:4-5; 32:39; 1 Samuel 2:2; 1 Kings 8:60).

Having seen that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are distinct Persons, that they are each fully God, and that there is nonetheless only one God, we must conclude that all three Persons are the same God. In other words, there is one God who exists as three distinct Persons.

If there is one passage which most clearly brings all of this together, it is Matthew 28:19: “Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.” First, notice that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinguished as distinct Persons. We baptize into the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Second, notice that each Person must be deity because they are all placed on the same level. In fact, would Jesus have us baptize in the name of a mere creature? Surely not. Therefore each of the Persons into whose name we are to be baptized must be deity.

Third, notice that although the three divine Persons are distinct, we are baptized into their name (singular), not names (plural). The three Persons are distinct, yet only constitute one name. This can only be if they share one essence.

Is the Trinity Contradictory?

This leads us to investigate more closely a very helpful definition of the Trinity which I mentioned earlier: God is one in essence, but three in Person. This formulation can show us why there are not three Gods, and why the Trinity is not a contradiction.

In order for something to be contradictory, it must violate the law of noncontradiction. This law states that A cannot be both A (what it is) and non-A (what it is not) at the same time and in the same relationship. In other words, you have contradicted yourself if you affirm and deny the same statement. For example, if I say that the moon is made entirely of cheese but then also say that the moon is not made entirely of cheese, I have contradicted myself.

Other statements may at first seem contradictory but are really not. Theologian R.C. Sproul cites as an example Dickens’ famous line, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Obviously this is a contradiction if Dickens means that it was the best of times in the same way that it was the worst of times. But he avoids contradiction with this statement because he means that in one sense it was the best of times, but in another sense it was the worst of times.

Carrying this concept over to the Trinity, it is not a contradiction for God to be both three and one because He is not three and one in the same way. He is three in a different way than He is one. Thus, we are not speaking with a forked tongue — we are not saying that God is one and then denying that He is one by saying that He is three. This is very important: God is one and three at the same time, but not in the same way.

How is God one? He is one in essence. How is God three? He is three in Person. Essence and person are not the same thing. God is one in a certain way (essence) and three in a different way (person). Since God is one in a different way than He is three, the Trinity is not a contradiction. There would only be a contradiction if we said that God is three in the same way that He is one.

So a closer look at the fact that God is one in essence but three in person has helped to show why the Trinity is not a contradiction. But how does it show us why there is only one God instead of three? It is very simple:

All three Persons are one God because, as we saw above, they are all the same essence. Essence means the same thing as “being.” Thus, since God is only one essence, He is only one being, not three. This should make it clear why it is so important to understand that all three Persons are the same essence. For if we deny this, we have denied God’s unity and affirmed that there is more than one being of God (i.e., that there is more than one God).

What we have seen so far provides a good basic understanding of the Trinity. But it is possible to go deeper. If we can understand more precisely what is meant by essence and person, how these two terms differ, and how they relate, we will then have a more complete understanding of the Trinity.

Essence and Person

Essence

What does essence mean? As I said earlier, it means the same thing as being. God’s essence is His being. To be even more precise, essence is what you are. At the risk of sounding too physical, essence can be understood as the “stuff ” that you “consist of.”

Of course we are speaking by analogy here, for we cannot understand this in a physical way about God. “God is spirit” (John 4:24). Further, we clearly should not think of God as “consisting of ” anything other than divinity. The “substance” of God is God, not a bunch of “ingredients” that taken together yield deity.

Person

In regards to the Trinity, we use the term “Person” differently than we generally use it in everyday life. Therefore, it is often difficult to have a concrete definition of Person as we use it in regards to the Trinity. What we do not mean by Person is an “independent individual” in the sense that both I and another human are separate, independent individuals who can exist apart from one another.

What we do mean by Person is something that regards himself as “I” and others as “You.” So the Father, for example, is a different Person from the Son because He regards the Son as a “You,” even though He regards Himself as “I.” Thus, in regards to the Trinity, we can say that “Person” means a distinct subject which regards Himself as an “I” and the other two as a “You.” These distinct subjects are not a division within the being of God, but “a form of personal existence other than a difference in being.”[3]

How do they relate? The relationship between essence and Person, then, is as follows. Within God’s one, undivided being is an “unfolding” into three personal distinctions. These personal distinctions are modes of existence within the divine being, but are not divisions of the divine being. They are personal forms of existence other than a difference in being.

The late theologian Herman Bavinck has stated something very helpful at this point: “The persons are modes of existence within the being; accordingly, the Persons differ among themselves as the one mode of existence differs from the other, and — using a common illustration —as the open palm differs from a closed fist.”[4]

Because each of these “forms of existence” are relational (and thus are Persons), they are each a distinct center of consciousness, with each center of consciousness regarding Himself as “I” and the others as “You.” Nonetheless, these three Persons all “consist of ” the same “stuff ” (that is, the same “what,” or essence). As theologian and apologist Norman Geisler has explained it, while essence is what you are, person is who you are. So God is one “what” but three “whos.”

The divine essence is thus not something that exists “above” or “separate from” the three Persons, but the divine essence is the being of the three Persons. Neither should we think of the Persons as being defined by attributes added on to the being of God. Wayne Grudem explains:

But if each person is fully God and has all of God’s being, then we also should not think that the personal distinctions are any kind of additional attributes added on to the being of God . . . Rather, each person of the Trinity has all of the attributes of God, and no one Person has any attributes that are not possessed by the others.

On the other hand, we must say that the Persons are real, that they are not just different ways of looking at the one being of God…The only way it seems possible to do this is to say that the distinction between the persons is not a difference of “being” but a difference of “relationships.” This is something far removed from our human experience, where every different human “person” is a different being as well. Somehow God’s being is so much greater than ours that within his one undivided being there can be an unfolding into interpersonal relationships, so that there can be three distinct persons.[5]

Trinitarian Illustrations?

There are many illustrations which have been offered to help us understand the Trinity. While there are some illustrations which are helpful, we should recognize that no illustration is perfect. Unfortunately, there are many illustrations which are not simply imperfect, but in error.

One illustration to beware of is the one which says, “I am one person, but I am a student, son, and brother. This explains how God can be both one and three.” The problem with this is that it reflects a heresy called modalism. God is not one person who plays three different roles, as this illustration suggests. He is one Being in three Persons (centers of consciousness), not merely three roles. This analogy ignores the personal distinctions within God and mitigates them to mere roles.

Benefits and Value of the Trinity

The Trinity is not merely an abstract theological concept; it holds immense practical and spiritual value for believers:

- Transformation: Understanding the Trinity helps us grasp the transformative power of divine love in our lives. We are invited to participate in the intimate relationship shared within the Trinity, experiencing personal growth, and deepening our connection with God.

- Unity and Diversity: The Trinity exemplifies the beauty of unity amidst diversity. It encourages us to embrace and celebrate our unique differences, while fostering love, respect, and cooperation within our communities.

- Divine Guidance: Through the Trinity, we gain access to divine wisdom and guidance. The Father’s wisdom, the Son’s teachings, and the Holy Spirit’s counsel navigate us through life’s challenges, offering comfort and direction.

- God’s Love Revealed: The Trinity showcases God’s ultimate expression of love for humanity. By understanding each person’s role, we comprehend the depth and vastness of divine love, drawing us closer to the heart of God.

Prepare to be enthralled by the profound depth and beauty that lies within the Trinity. As we explore the biblical foundations, the uniqueness of its members, and the extraordinary benefits it brings, a deeper understanding of God’s divine nature awaits. Enter a realm of awe and wonder as we unravel this captivating mystery together.

Trinity in the Bible verse

In the Christian tradition, the Trinity is an important part of the faith. It is the belief that God is one, yet manifests himself as three distinct divine persons – God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. While this concept of the Trinity may not seem obvious in the Bible, there are several verses that point to it.

One of the early references to the Trinity is found in the Gospel of Matthew, when Jesus instructs his disciples on prayer: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19 ESV). This verse serves as an early teaching of the three persons of the Godhead, as Jesus instructs his followers to baptize in the name of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Another early reference to the Trinity occurs in the book of Isaiah, when the prophet proclaims: “The LORD of Hosts is one, and yet he is the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit” (Isaiah 48:16-17 ESV). This verse is significant in affirming the oneness of God, while also recognizing the three distinct persons of the Trinity.

The concept of the Trinity is further solidified in the book of John, when Jesus is preparing for his death and departure. On his last day with his disciples, Jesus prays: “that they may be one, even as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me” (John 17:22-23 ESV). Here, Jesus prays to the Father, affirming the oneness of God while also recognizing the distinct persons of the Trinity.

Lastly, the Apostle Paul’s letters provide further insight into the nature of the Trinity. In 1 Corinthians 12:4-6, Paul states that “there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of service, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who empowers them all in everyone.” This establishes the three persons of the Trinity in distinct terms – the Spirit, the Lord (Jesus), and God (the Father).

Each of these verses, and many others, point to the important doctrine of the Trinity in the Bible. Through these verses, we get a glimpse into the complex yet unified nature of God.

1. John 1:1–5

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

In the beginning was the Word echoes the opening phrase of the book of Genesis, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” John will soon identify this Word as Jesus (John 1:14), but here he locates Jesus’ existence in eternity past with God. The term “the Word” (Gk. Logos) conveys the notion of divine self-expression or speech and has a rich OT background. God’s Word is effective: God speaks, and things come into being (Gen. 1:3, 9; Ps. 33:6; 107:20; Isa. 55:10–11), and by speech he relates personally to his people (e.g., Gen. 15:1). John also shows how this concept of “the Word” is superior to a Greek philosophical concept of “Word” (logos) as an impersonal principle of Reason that gave order to the universe. And the Word was with God indicates interpersonal relationship “with” God, but then and the Word was God affirms that this Word was also the same God who created the universe “in the beginning.” Here are the building blocks that go into the doctrine of the Trinity: the one true God consists of more than one person, they relate to each other, and they have always existed. From the Patristic period (Arius, c. A.D. 256–336) until the present day (Jehovah’s Witnesses), some have claimed that “the Word was God” merely identifies Jesus as a god rather than identifying Jesus as God, because the Greek word for God, Theos, is not preceded by a definite article. However, in Greek grammar, Colwell’s Rule indicates that the translation “a god” is not required, for lack of an article does not necessarily indicate indefiniteness (“a god”) but rather specifies that a given term (“God”) is the predicate nominative of a definite subject (“the Word”). This means that the context must determine the meaning of Theos here, and the context clearly indicates that this “God” that John is talking about (“the Word”) is the one true God who created all things (see also John 1:6, John 1:12, John 1:13, John 1:18 for other examples of Theos without a definite article but clearly meaning “God”).

All things includes the whole universe, indicating that (except for God) everything that exists was created and that (except for God) nothing has existed eternally. Made through him follows the consistent pattern of Scripture in saying that God the Father carried out his creative works through the activity of the Son (cf. 1 Cor. 8:6; Col. 1:16; Heb. 1:2). This verse disproves any suggestion that the Word (or the Son, John 1:14) was created, for the Father would have had to do this by himself, and John says that nothing was created that way, for without him was not any thing made that was made.

2. John 10:30

“I and the Father are one.

Jesus’ claim that I and the Father are one (i.e., one entity—the Gk. is neuter; cf. John 5:17–18; John 10:33–38) echoes the Shema, the basic confession of Judaism, whose first word in Deut. 6:4 is shema‘ (Hb. “hear”). Jesus’ words thus amount to a claim to deity. Hence, the Jews pick up stones to put him to death. Jesus’ unity with the Father is later said to constitute the basis on which Jesus’ followers are to be unified (John 17:22). As in 1:1, here again the basic building blocks of the doctrine of the Trinity emerge: “I and the Father” implies more than one person in the Godhead, but “are one” implies that God is one being.

3. Genesis 1:26

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.

Let us make man in our image. The text does not specify the identity of the “us” mentioned here. Some have suggested that God may be addressing the members of his court, whom the OT elsewhere calls “sons of God” (e.g., Job 1:6) and the NT calls “angels,” but a significant objection is that man is not made in the image of angels, nor is there any indication that angels participated in the creation of human beings. Many Christians and some Jews have taken “us” to be God speaking to himself, since God alone does the making in Gen. 1:27 (cf. Gen. 5:1); this would be the first hint of the Trinity in the Bible (cf. Gen. 1:2).

4. Matthew 28:18–20

And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.

The imperative (make disciples, that is, call individuals to commit to Jesus as Master and Lord) explains the central focus of the Great Commission, while the Greek participles (translated go, baptizing, and “teaching” [Matt. 28:20]) describe aspects of the process. all nations. Jesus’ ministry in Israel was to be the beginning point of what would later be a proclamation of the gospel to all the peoples of the earth, including not only Jews but also Gentiles. The name (singular, not plural) of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is an early indication of the Trinitarian Godhead and an overt proclamation of Jesus’ deity.

5. 2 Corinthians 13:14

The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all.

The only Trinitarian benediction in Paul’s letters, stressing that grace, love, and fellowship with one another come from God in Christ through the Spirit. Paul’s final reference to the Spirit recalls that he is writing and praying as a minister of the new covenant (see 2 Cor. 1:22; 2 Cor. 3:3–18; 2 Cor. 4:13–18; 2 Cor. 5:5). you all. A final stress on the unity of the reconciled church, brought about by God himself, the furthering of which was one of the main goals of Paul’s letter (2 Cor. 1:7; 2:5–11; 2 Cor. 5:18–6:2; 2 Cor. 6:11–13; 2 Cor. 7:2–4; 2 Cor. 9:13–14; 2 Cor. 12:19; 2 Cor. 13:5–10).

6. Deuteronomy 6:4

“Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.

Hear, O Israel. This verse is called the Shema from the Hebrew word for “Hear.” The LORD our God, the LORD is one. The Lord alone is Israel’s God, “the only one.” It is a statement of exclusivity, not of the internal unity of God. This point arises from the argument of ch. 4 and the first commandment. While Deuteronomy does not argue theoretically for monotheism, it requires Israel to observe a practical monotheism (Deut. 4:35). This stands in sharp contrast to the polytheistic Canaanites.

7. Hebrews 1:1–4

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. After making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high, having become as much superior to angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs.

Four points of contrast occur between Heb. 1:1 and 2: time of revelation (“long ago” vs. these last days); agent of revelation (“prophets” vs. Son); recipients of revelation (“fathers” vs. us); and, implicitly, the unity of the final revelation in the Son (cf. the “many times and in many ways” in Heb. 1:1, implying, by contrast, that this last revelation came at one time, in one way, in and through God’s Son). Since God has spoken finally and fully in the Son, and since the NT fully reports and interprets this supreme revelation once the NT is written, the canon of Scripture is complete. No new books are needed to explain what God has done through his Son. Now believers await his second coming (Heb. 9:28) and the city to come (Heb. 13:14). Jesus is heir of all things (i.e., what he “inherits” from his Father is all creation) by virtue of his dignity as Son (Heb. 1:4). The preexistence, authority, power, and full deity of the Son are evident in his role in creating the world; cf. John 1:3, 10; Col. 1:16.

8. Matthew 3

The Spirit of God anoints Jesus as Israel’s King and Messiah and commissions him as God’s righteous “servant” (cf. Isa. 42:1).

The voice from heaven confirms the eternally existing relationship of divine love that the Son and Father share as well as Jesus’ identity as the messianic Son of God (Ps. 2:7). This beloved Son is the triumphant messianic King, yet he is also the humble “servant” into whose hands the Father is well pleased to place the mission to bring salvation to the nations (Isa. 42:1–4).

9. John 14:10

Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me? The words that I say to you I do not speak on my own authority, but the Father who dwells in me does his works.

I am in the Father and the Father is in me. Though there is a complete mutual indwelling of the Father and the Son, the Father and the Son remain distinct persons within the Trinity, as does the Holy Spirit (Matt. 28:19; 2 Cor. 13:14), and the three of them still constitute only one Being in three persons.

10. 2 Corinthians 3:17

Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.

the Lord is the Spirit. Different explanations have been offered for this difficult and compressed statement: Paul may be saying that Christ and the Spirit function together in the Christian’s experience—i.e., that the Lord (Christ) comes to us through the ministry of the Spirit (though they are still two distinct persons). Another view (based on the reference in v. 16 to Ex. 34:34, “Moses went in before the LORD to speak with him”) is that the “Lord” here refers to Yahweh (“the LORD”) in the OT (that is, God in his whole being without specifying Father, Son, or Spirit). In this case, Paul is saying that Yahweh in the OT is not just Father and Son, he is also Spirit. In either case, Paul’s primary point seems to be that the Christian’s experience of the ministry of the Spirit under the new covenant (2 Cor. 3:3–8) is parallel to Moses’ experience of the Lord under the old covenant—i.e., that the Spirit (under the new covenant) sets one free from the veil of hard-heartedness (vv. 12–15). Paul regularly distinguishes Christ from the Holy Spirit in his writings, and that is surely the case even here, since later in this verse he speaks of the Spirit of the Lord. Moreover, it should not be supposed that Paul is teaching that any of the members of the Trinity (the Father, the Son, or the Spirit) are the same person, which would be the heresy of modalism; instead Paul is stressing the gracious unity of purpose among the three persons of the Trinity. There is freedom, though unspecified in the context, most likely refers to the many kinds of freedom that come with salvation in Christ and with the presence of the Holy Spirit: that is, freedom from condemnation, guilt, sin, death, the old covenant, and blindness to the gospel, as well as freedom that gives access to the loving presence of God.