The world of Wonderland is chaotic, but it is also deeply spiritual. The Cheshire Cat, for example, is a symbol of the divine feminine and wisdom. Before we go further, let us look at the Spiritual meaning of Alice in Wonderland, Alice in Wonderland hidden meaning, and Alice in Wonderland character symbolism. The Caterpillar takes Alice on a journey through her childhood memories, which helps her to understand herself better and grow as a person. And when Alice finally drinks the potion that will make her taller than all the other characters in Wonderland, she gains wisdom and perspective that allow her to see things in a new way.

The story of Alice in Wonderland is a tale about the journey of a girl who is thrust into a strange new world and must find her way out. It’s also a story of how we can learn to see our own stories in new ways and how we can find the power within ourselves to create the lives we want.

Alice’s journey begins when she falls down a rabbit hole into a whole new world. She finds herself in a place where time moves differently than it does for her at home, where people have names like “Cheshire Cat” and “Mad Hatter,” where everything seems upside down and backwards.

Alice is completely unprepared for this strange new reality, but she manages to find some comfort in it anyway by befriending some creatures who live there. The white rabbit who leads her down the hole shows her kindness and helps guide her through his part of Wonderland; she meets Tweedledee and Tweedledum, who seem like silly but harmless twins; and she meets other creatures who are kind to her as well—a caterpillar who teaches her lessons about change; the Cheshire Cat, who helps guide Alice through Wonderland with clues only he can provide;

Spiritual Meaning of Alice In Wonderland

The spiritual meaning of Alice in Wonderland is a complex and fascinating topic. The book was originally published in 1865, but it’s still widely read today for its compelling story and imaginative characters.

Alice follows a young girl on an adventure through Wonderland—a magical world inhabited by talking cats, card soldiers, and other strange creatures. She meets many of these creatures along the way and has to figure out how to get home in the process.

This book was written at a time when people were starting to question their faith in religion and God. It’s no coincidence that the plot takes place in a fantastical world where there is no God or any sort of divine presence. This is because Carroll felt like he had lost faith in his religion and wanted to explore what would happen if there was no divine influence on our lives at all.

He also wrote this book while he was going through some personal difficulties in his own life, so it’s possible that he was trying to make sense of those issues through his writing as well; however, I would recommend reading other sources before drawing any conclusions about this author’s motivations or intentions with Alice in Wonderland!

In the spiritual meaning of Alice in Wonderland, Alice is a girl who has been led astray by her desires and her curiosity. She has already gone through the looking glass and into the world of dreams, where she finds herself at a tea party with small cakes and tiny cakes. She eats them all up without thinking about how many there are or whether it’s possible for her to eat that many. The White Rabbit takes her to see the Mad Hatter, who is late because he was helping an old lady across the street. The old lady turns out to be herself, who had forgotten about being late for the tea party.

Alice then finds herself on a chessboard, where she meets Tweedledee and Tweedledee’s twin brother, Tweedledee (who is also called Dum). They tell her that they’re going to play a game of croquet with flamingos instead of balls because they don’t have enough balls.

The next day they play croquet again, but this time Tweedledee starts crying because he doesn’t want to play anymore—he misses his baby sister! So they all go back inside their house… except for Alice

What is The Main Theme of Alice in Wonderland

The book Alice in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll, has been part of many children’s lives. It seems like a simple fairy tale, but it goes much deeper than that.

The events in the story correlate with the steps in a child’s growth and progression through childhood and adolescence. According to editors Charles Frey and John Griffin, “Alice is engaged in a romance quest for her own identity and growth, for some understanding of logic, rules, the games people play, authority, time, and death.” When you approach the book with this idea in mind, it offers interesting and meaningful interpretations of the events and characters in the story.

“Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Illustration to the fourth chapter, by John Tenniel. Wood engraving by Thomas Dalziel.

How puzzling all these changes are! I’m never sure what I’m going to be, from one minute to another.

Spiritual Meaning of Alice In Wonderland In Dream

At the beginning of Alice in Wonderland, Alice daydreams and is unable to pay attention while her sister reads an advanced novel to her. Alice’s mindset is childlike and distractible. While her imagination runs wild, she begins to piece together a perfect world of her own. That’s when Alice notices a white rabbit, a manifestation of her imagination that sparks her curiosity.

“Alice follows the rabbit because she is ‘burning with curiosity.’ Soon she finds things becoming ‘curiouser and curiouser.'”

Children are usually the people with the most curiosity; they are the ones who are always eager to learn more.

Later, Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum tell her the tale of the Curious Oysters, which is about how curiosity can lead to terrible consequences. This shows how adults often use stories to control children with fear and to destroy children’s sense of imagination and curiosity by telling them to quit asking questions and grow up. Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum symbolize parents who are trying to keep Alice’s imagination in check.

If it had grown up, it would have made a dreadfully ugly child; but it makes rather a handsome pig, I think.

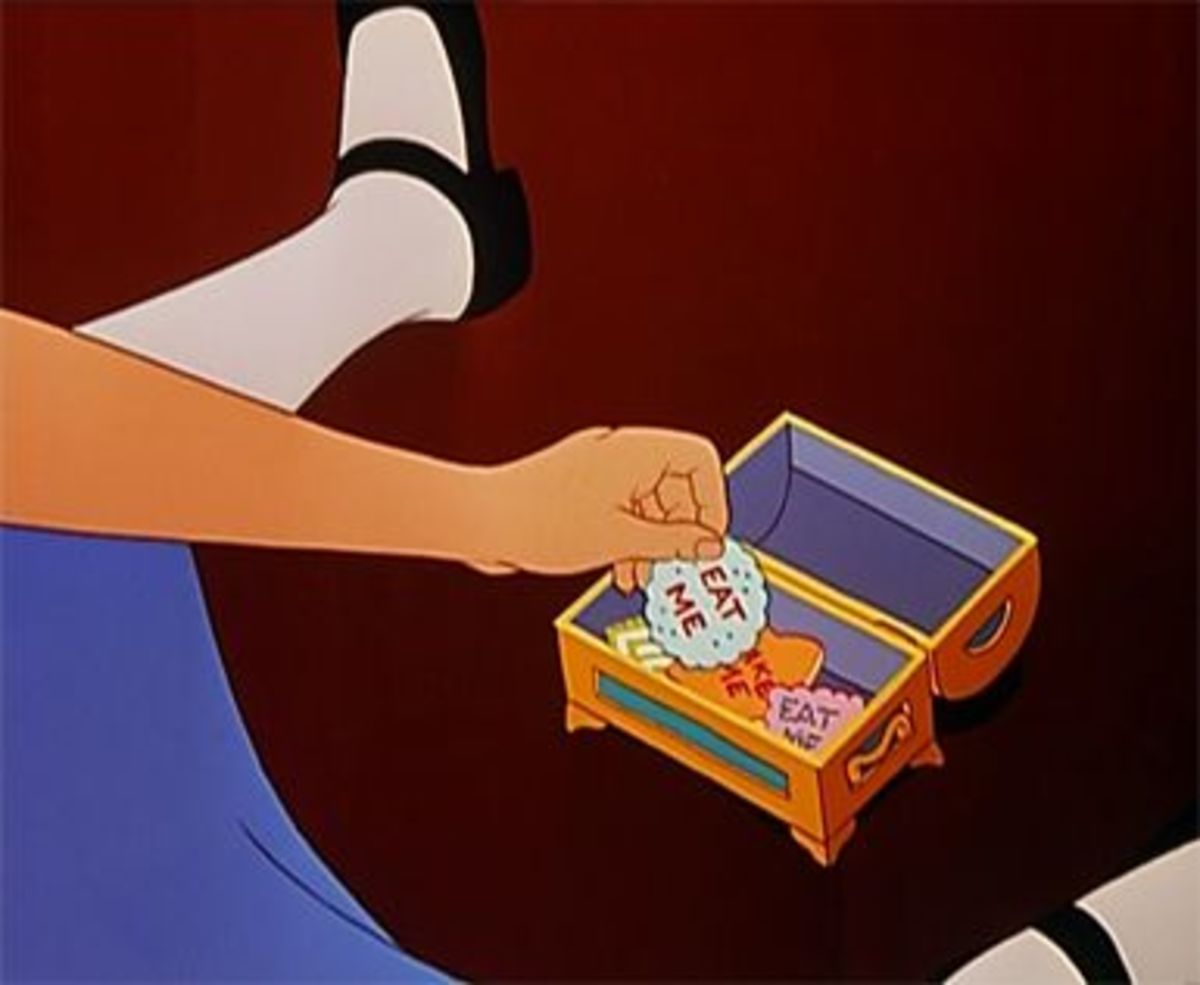

“Eat Me”

Alice gets in trouble because of her curiosity. The white rabbit tells her to run into the house to quickly fetch his gloves. While searching for them, she opens a cookie jar only to find a cookie with “Eat Me” written on it. Without thinking twice, she consumes the cookie.

Alice is still in her childhood stage and needs an adult figure to guide her. At this moment, there is no such figure. “We view children as needing gentle guidance if they are to develop emotionally, intellectually, morally, even physically.” (Henslin)

Alice’s eating of the cookie represents two very important ideas. The first is, again, how curiosity gets one into trouble. She eats the cookie after being told the tale of the Curious Oysters, because a child will sometimes disobey and do something even after being told it is wrong. By eating the cookie, she demonstrates Kohlberg’s first theory of moral development, stage one of the preconventional level, which states that “right is whatever avoids punishment or gains reward” (Wood). Because there was no parent or adult figure around, curiosity prevailed against better judgment, and she ate the cookie.

This situation may also be about peer pressure while growing up. Inside the cookie jar were many cookies with labels with different instructions; the cookies were all telling her what to do. Just like everyone does at some point, she gives in to peer pressure. As a consequence, she grows rapidly into a giant. The white rabbit and other characters she encounters perceive her giant self as a monster instead of a little girl. A society may perceive youngsters who give into peer pressure, for example who take drugs or experiment in other reckless ways, as monstrous.

On many occasions, Alice shows her juvenile nature, her child-like thinking, and confusion. When she first falls down the rabbit hole and is confronted by the door, she gives herself “some good advice,” saying, “For if one drinks much from a bottle marked poison, it is almost certain to disagree with one sooner or later.” The door responds, “I beg your pardon,” with a confused look on its face. In a relationship between a young child and an adult, the adult is often unable to comprehend the child’s logic. It isn’t until the formal operations stage, at age 11 or 12, that the child is able to “apply logical thought to abstract, verbal, and hypothetical situations,” (Wood). Obviously, Alice has not yet achieved this level of thinking.

Shortly after Alice enters Wonderland, she encounters something else that makes no sense to her. When she is wet after being washed up onto the shore, she listens to a dodo bird, who tells her to run in a circle with everyone else in order to dry off. What he is telling her to do makes no sense whatsoever, because the water keeps engulfing them, but she continues to do it anyway. By blindly obeying the adult figure, she exposes her childlike ignorance.

Later in the book, Alice is confronted with another confusing situation. The White King is waiting for his messengers and asks Alice to look along the road to see if they are coming. “I see nobody on the road,” says Alice. “‘I only wish I had such eyes,’ the King remarked in a fretful tone. ‘To be able to see nobody! And at that distance too! Why, it’s as much as I can do to see real people, by this light.”

This somewhat exemplifies the preoperational stage of childhood, which includes symbolic function, meaning that one thing can stand for another (Wood). Apparently, the author is trying to get a point across that “nobody” can stand for a person as well as “nothing.” Here is another lack of understanding between adults and children, but this time, the adult’s statement seems easier to comprehend for Alice, and makes, surprisingly, more sense than her previous realization. This shows how she is mentally progressing towards the formal operations stage, little by little.

I wonder if I’ve been changed in the night. Let me think. Was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I’m not the same, the next question is ‘Who in the world am I?’ Ah, that’s the great puzzle!

“Who Are You?” “I —Hardly Know.”

As Alice progresses through her dream, she loses her sense of identity, just as most people do when they hit adolescence.

“When the Caterpillar asks Alice, ‘Who are you,’ and Alice can barely stammer out a reply, `I—hardly know,’ then Carroll is exposing the quintessential vulnerability of the child whose growth and knowledge of self and the world vary so greatly from day to day that a sense of answerable identity becomes highly precarious, if not evanescent.” (Frey).

At this point in the story, Alice has reached an age where she has lost her identity—that is, adolescence.

“In the industrialized world, children must find themselves on their own… They attempt to carve out an identity that is distinct from both the ‘younger’ world being left behind and the ‘older’ world that is still out of range” (Henslin). The caterpillar doesn’t ever give Alice any direction, and she is now forced to find out who she is on her own.

“[She] is rarely aided by the creatures she meets. Whereas in a tale of Grimms, Andersen or John Ruskin, the protagonist’s meeting with a helpful bird or beast would signal his or her charity toward the world or nature” (Frey). In Alice in Wonderland, unlike other fairy tales, the story represents a child’s true progression through life. In real life, in the industrialized world, a child has to figure things out on her own.

In sociology, there is a stage called transitional adulthood. This is a period where young adults “find themselves; young adults gradually ease into responsibilities; they become serious.” (Henslin) By the end of the story, Alice has learned to deal with her problems and has regained sight of her identity. The queen, who loses her temper and wants to kill Alice, is the obstacle that finally helps Alice become an adult. To leap over this obstacle, she reaches into her pocket to find a mushroom from earlier, eats it, and grows to an enormous size. This most likely represents how she is facing her fear and taking on responsibility, or “growing up.”

Alice in Wonderland is a perfect example of childhood through adolescence. Just as a child’s life is filled with good and bad choices, Alice’s is, too. As most do, she learns from her experiences and ultimately becomes more mature—emotionally, in how she deals with her problems, and in the way she perceives different situations, all of which are encompassed in the progression of a child.

“I’m afraid I can’t explain myself, sir. Because I am not myself, you see?”

Dark Story Behind Alice In Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland is the classic story of a young girl who falls down a rabbit hole and finds herself in a strange, fantastical world. It’s one of the best-known children’s stories of all time, and it has inspired countless adaptations, including Disney’s 1951 animated film.

But the original book, written by Lewis Carroll, was not just for kids—it was also full of hidden meaning. The rabbit hole that Alice falls down is really a metaphor for the birth canal; when she enters it, she becomes an adult woman who enters adulthood through death (the rabbit hole). This concept is echoed in other works, like Dante’s Inferno, where he describes hell as being at the bottom of a cavernous pit.

The flowers that grow out of the ground in Wonderland represent different stages of life; some are wildflowers representing youth, others are more mature plants representing adulthood.

“Alice in Wonderland” is a classic story that has been read by children for years. The story follows Alice as she falls down a rabbit hole and finds herself in a strange new world. The story can be seen as an allegory, where the characters represent different ideals or ideas. For example, Alice represents innocence and curiosity, while the queen represents jealousy and greed. This can be seen when the queen tells Alice, “Off with her head!”